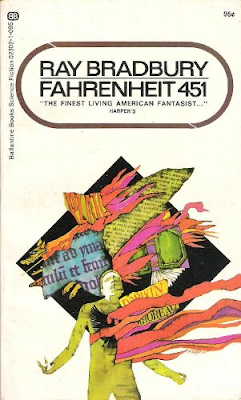

Fahrenheit 451

Ray Bradbury

Mass-Market Paperback, 171 pages Ballantine, 1971

(first published 1953)

Dystopian Fiction, Science Fiction

Literary awards: Hugo Award for Best Novel (1954), Prometheus Hall of Fame Award (1984)

Ray Bradbury’s books make for immediate, mesmerizing, entirely compulsive reading. His prose is electrifying in its use of poetic metaphor and dramatic syntax. The reader is instantly plunged into an alien culture, or a terrifying future, and is not really released even after the last page is turned.

I had been postponing reading this novel for years. I am, after all, a confirmed bibliophile. Reading a novel with a plot involving the burning of books would, I kept telling myself, be too traumatic for me.

I finally decided to wade in.

Need I say that I only put the book down when I absolutely had to, when reality intruded? The novel carried me along on its relentless wave of narrative. Of course, I tried not to picture the books burning as I read, but Bradbury wouldn’t let me. Not when he was describing them as living creatures, dying, their pigeon wings flapping…. The fact that I managed to endure this at all is a real tribute to the greatness of his writing.

The characters are indelibly imprinted on my brain. The most compelling, of course, is the protagonist, Montag. Equally compelling are Faber, who is obviously Montag’s alter ego, and the numinous Clarisse. She is the one who first awakens Montag to the futility of denying his own soul, the stirrings of thought and penetrating questions that reading invariably arouses. The most tragic character is Beatty, who struggles hard against his love of books, in his work as chief fireman. This struggle culminates in a final, ironic conflagration. Montag’s wife, Mildred, is to be pitied, since she is unable to acknowledge her emptiness, her consuming loneliness. She pushes away the power and beauty to be found in books. She refuses to come out of denial, preferring ‘the family’, a banal cast of characters she endlessly watches in the living room ‘wall-to-wall TV’, in order to anesthetize the deepest longings of her soul.

As I read, I became aware of a deeper sense of discomfort, underneath that elicited by the burning of books. Due to my own life experiences, I, along with this disturbed society, had been unconsciously longing for a world in which no one would ever get his or her feelings hurt – a world where everyone’s rights would be respected, especially those of minorities.

Bradbury gave me a sobering look at such a world, and it was absolutely terrifying. It was “American Idol” gone wild, a world in which people no longer thought, felt, or even communicated on a soul level with other human beings. Instead, they spent all their time being ‘happy’, through mindless, ongoing entertainment.

I realized that I didn’t want to live in such a world; it would mean the total annihilation of what makes us most deeply human – the ability to dream, to wonder, to ponder the deep truths of life.

Books and the questions they raise are incompatible with living in a world where nobody would offend anyone else. Books disturb, probe, anger and challenge. Books are flawed at times, due to their authors’ all-too-human penchant for furthering their own pet theories, however twisted they might seem to a reader. Books can make us squirm, for they can force us to face the unwanted realities we try to bury.

There is still a part of me that thinks that books such as “Mein Kampf” should be burned, or at least, allowed to expire by going, and staying, out of print. The Marquis de Sade also comes to mind as an author of books with a markedly offensive subject matter. Then there’s Anais Nin. One of her books chronicles the incestuous relationship she had with her father…

The problem is, where do you draw the line? Who decides which books merit extinction?

I don’t have a final, satisfactory answer.

And so I am left feeling restless and slightly depressed, although I’m glad to have read the book, nevertheless. It has caused me to ponder what I really and truly believe regarding the banning of books, and their potentially harmful influences.

Yet another uncomfortable element of the plot is Montag’s desperate, evil act toward the end of the novel. I suppose it is inevitable, however. It is indeed immoral, but then, so is the entire, nihilistic society he is a part of. It is the act of a man who has turned on a symbol of that society, and so, turned on himself, in a sense, in order to be reborn as a new man, a man who thinks and feels, even if doing so causes him some measure of unhappiness. This act could, itself, be considered a harmful influence on a reader, since Montag evades punishment. Yet, as an act of rebellion, of a misplaced sort of justice, it is totally fitting. Therein lies “the treason of the artist”, as Ursula K. LeGuin puts it. For the artist makes meaning out of pain, suffering, and tragedy. This is also part of the value to be found in books.

The symbol of rebirth is ubiquitous in the novel. At one point, the myth of the Phoenix is mentioned. Ironically, civilization is being reborn out of the very fire it has used to destroy the very objects that had given it meaning – books.

By the end of the novel, groups of people have quietly begun the reconstruction, the return to reading. It is a movement that is slowly gathering momentum. Civilization, suggests Bradbury, as Miller’s Canticle for Leibowitz was to do years later, is constantly rising from the ashes of every Dark Age in order to reinvent itself.

So I know that I will be re-reading this book sometime in the near future, as I intend to do with Miller’s. Both are books that apparently dwell on despair, only to end with a feeling of hope.

Bradbury has once again sparked my imagination and tickled my intellect. He also refuses to let me forget his incredible take on a future that may or may not turn out to become all too real.

I've read this book, and am reading another Bradbury now - Something Wicked This Way Comes. I like how you call his prose electrifying and poetic. I think he is one of those authors that show, not tell. Fahrenheit is definitely a tough read for us booklovers, but I think it's one of the best classic dystopias.

ReplyDeleteHi, Riv!

DeleteThanks for the compliment! Bradbury is a great prose master, and I agree -- he shows. Sometimes terrifyingly so. And you're right -- this novel is one of the best classic dystopias!

I was so sad when I heard about Bradbury's passing...I really must get all of his books, and read them all, in spite of the thread of horror to be found in some of them. An example is the one you're reading now. But he is definitely unsurpassed!!

Thanks for the comment, and for participating in my giveaway!! :)

I was so sad too when I heard about his passing. He seemed like one of those authors who is also a genuinely nice person in addition to being an awesome writer (not all of them are like that, hehe). I finished "Something Wicked..." yesterday and right after went online to plan purchase of some of his other novels and stories :)

DeleteI wish you a happy spring and the beginning of summer! :)